During last year’s immersion in matters of health care, the US system was frequently compared to those of Canada, the UK, Japan, Australia, and Western European countries. Whether the comparison involved infant mortality, lifespan, or comprehensive coverage, the US fell far behind these other developed countries.

During last year’s immersion in matters of health care, the US system was frequently compared to those of Canada, the UK, Japan, Australia, and Western European countries. Whether the comparison involved infant mortality, lifespan, or comprehensive coverage, the US fell far behind these other developed countries.

The lack of universal coverage is perhaps the most disturbing difference. There are clearly economic advantages to universal health care: Diseases cost less in the long run when they’re prevented or caught early; insurance costs less when it draws from a pool that includes both the healthy and the less healthy.

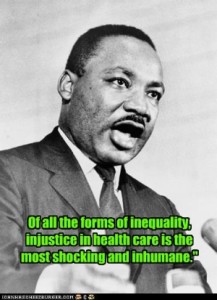

Universal coverage is an ethical issue. The US claims to be a country that values equal opportunity. If you lack adequate health care from the time you’re conceived, however, your opportunities will never be equal.

Inequality and the redistribution of wealth

All these recent discussions and comparisons have prompted Europeans to reflect on their own health care systems and to offer an explanation for the difference. According to Joseph Kutzin of the World Health Organization (WHO), the basic difference in European and American health care is that Europe has a well-managed system. whereas the US is hopelessly fragmented. The US has “no coherent regulatory framework for either universal coverage or cost control,” according to Kutzin. European systems recognize the need for limits on health care spending. In America we call that “death panels.”

Martin McKee, a London professor of European Public Health, comments on the role of inequality. Whether inequality is due to race, poverty, gender, unemployment, or age, the only way to increase equality is through state intervention. The way Europeans see it: “It’s a rule of thumb that if you are rich, you are unlikely to need much health care, and if you are poor you are likely to need it. So there’s redistribution from rich to poor, but also from people of working ages to those who are not, and in reproductive ages from males to females–health care inevitably involves redistribution.”

Many Americans are adamantly opposed to the idea of redistribution. Some of this gets chalked up to our rugged individualism. But much of it is simply an unwillingness to recognize the structural causes of poverty. 71 percent of Americans believe the poor could escape poverty if they worked hard enough. That figure is only 40 percent in Europe. Only 30 percent of Americans believe luck determines income, versus 54 percent in Europe.

Is race the elephant in the room?

Some of the discrepancy between European and American health care systems can be explained by historical differences. Europeans not only have a longer history, but a more violent one. Antonio Duran, a consultant for WHO and an expert on Eastern Europe, comments:

Western Europeans are rich enough now, with their history of revolution, war and conflict behind them, to hear a clear message that either they protect the poor–or else… Europeans know that if you go too far one way or the other you pay a price, either in terms of social cohesion and unrest, or in terms of health indicators.

In the US, we had the Civil War, but what did we learn? We still have racism, and it’s still a major determinant of health. Here’s Martin McKee again (emphasis added):

There is an association in the US between low life expectancy and income inequality, but that is driven largely by the southern states. But there are correlations with other factors like race or class, so it’s a complex issue. … In Europe we had a post-war settlement with social welfare systems because the élite realised from their experiences in the war that they might have a schloss or chateau one day but nothing the next, so they organised things so that wherever they ended up it would be tolerable at least! But in the US, if you are rich you are likely to be white, and you know there’s no chance that you’ll wake up the next morning black! So I think race is the elephant in the room in the US. I find there is a real reluctance to discuss this in the US — people don’t want to get into it, on either side.

That’s not quite a fair assessment. US medical journals are full of statistics on the negative health consequences of being black and/or poor. It’s true, however, that the issue hasn’t been adequately addressed in public discussions of health care, that is, in the popular media.

Due to the Massachusetts election – and the political nature of health care reform in the US – we’re still having those discussions. So perhaps there’s still time to point to the elephant and give it a name. It’s a historical opportunity for Americans that we shouldn’t miss.

Related posts:

The Economist reviews Kaiser Permanente health care

Getting health care right: Paris and Amsterdam

How Australia does preventive health care

A reason for health care reform

Why is it so hard to reform health care? Rugged individualism

Why is it so hard to reform health care? The historical background

The health care debate: Seeing ourselves through the eyes of others

Robbing Peter to Pay Paul: The health care shell game

Universal health care: What would Socrates do?

Were “death panels” a teachable moment for palliative care?

The need for health and the right to health

Sources:

Robert Walgate, European health systems face scrutiny in US debate, The Lancet, Vol. 374 No. 9600 p. 1407-1408, October 24, 2009

Mark R. Rank, Hong-Sik Yoon, Thomas A. Hirschl, American poverty as a structural failing: evidence and arguments, Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, December 2003

Elizabeth Gudrais, Unequal America: Causes and consequences of the wide–and growing–gap between rich and poor, Harvard Magazine, July/August 2008

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.